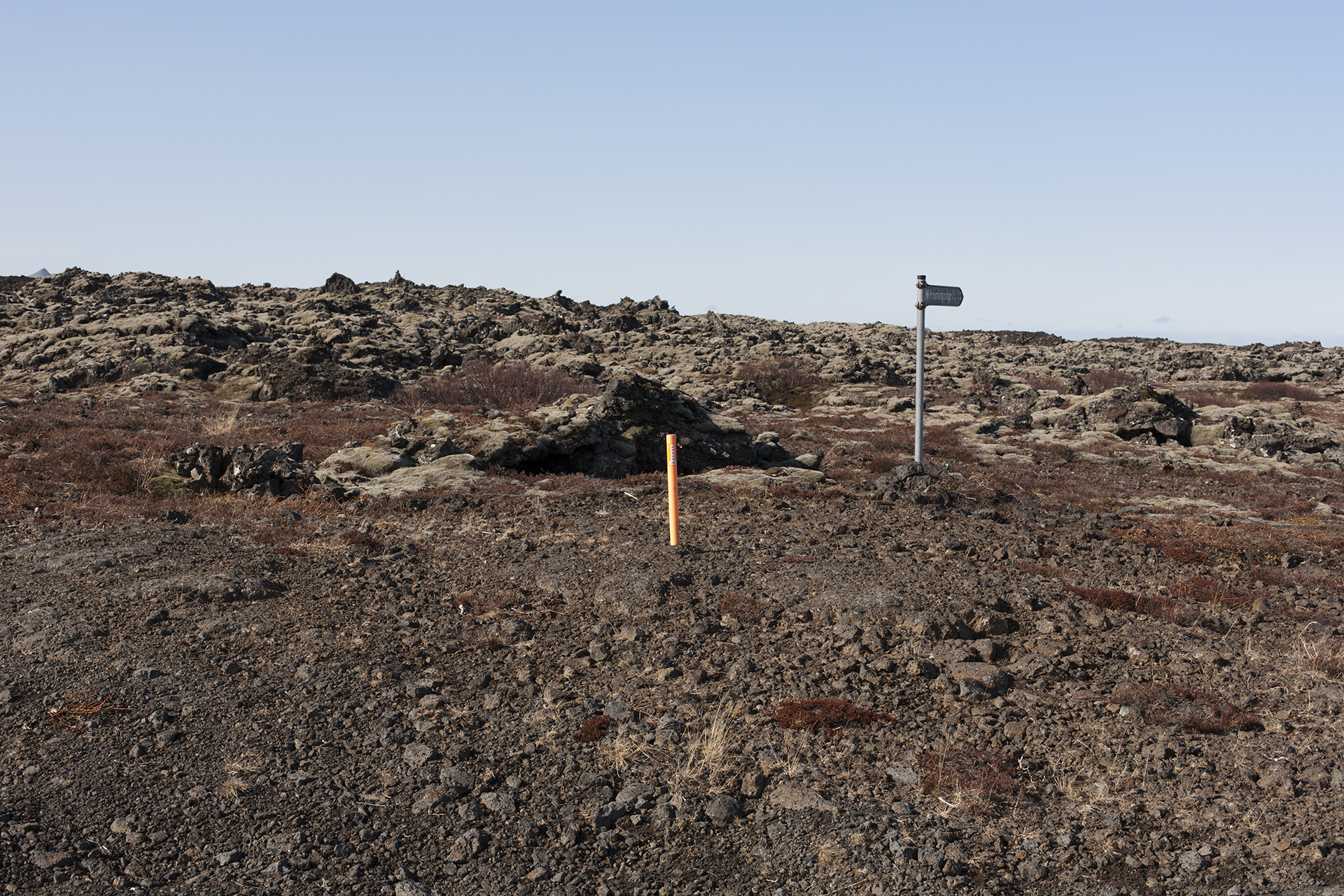

Hraun I

SW Iceland, 2015

What does “nature” look like? Can I get close enough to photograph it? And once I’d have captured “nature”, how can I be sure that I haven’t altered its essence in any way?

With a reasonable fluency in Icelandic, I went off the roads the Icelandic tourist industry paved for us foreign visitors. Caught in a dense network consisting of place names, maps, power lines, quarries and roads, the idea that there was a pristine nature on the other side of the impeccable brochures or websites became seriously dubious. That was in late 2013.

I came back in June 2014 and the Spring of 2015 informed and inspired by the discussions around the Anthropocene. I then set out to focus my attention on the Reykjanes peninsula in southwest Iceland, a relatively small area where two thirds of the country’s population live, thus where the pressure on the environment is felt and seen the most.

Affected by the not so uncommon urban sprawl and a furrowed by the North Atlantic ridge at the same time, the peninsula seemed torn apart between an avid desire to develop and a careful attention to the Earth tremors or the whispers of “hidden people” (Huldufólk in Icelandic).

I further explored the places, forms and residues that make nature tourism in Iceland possible.

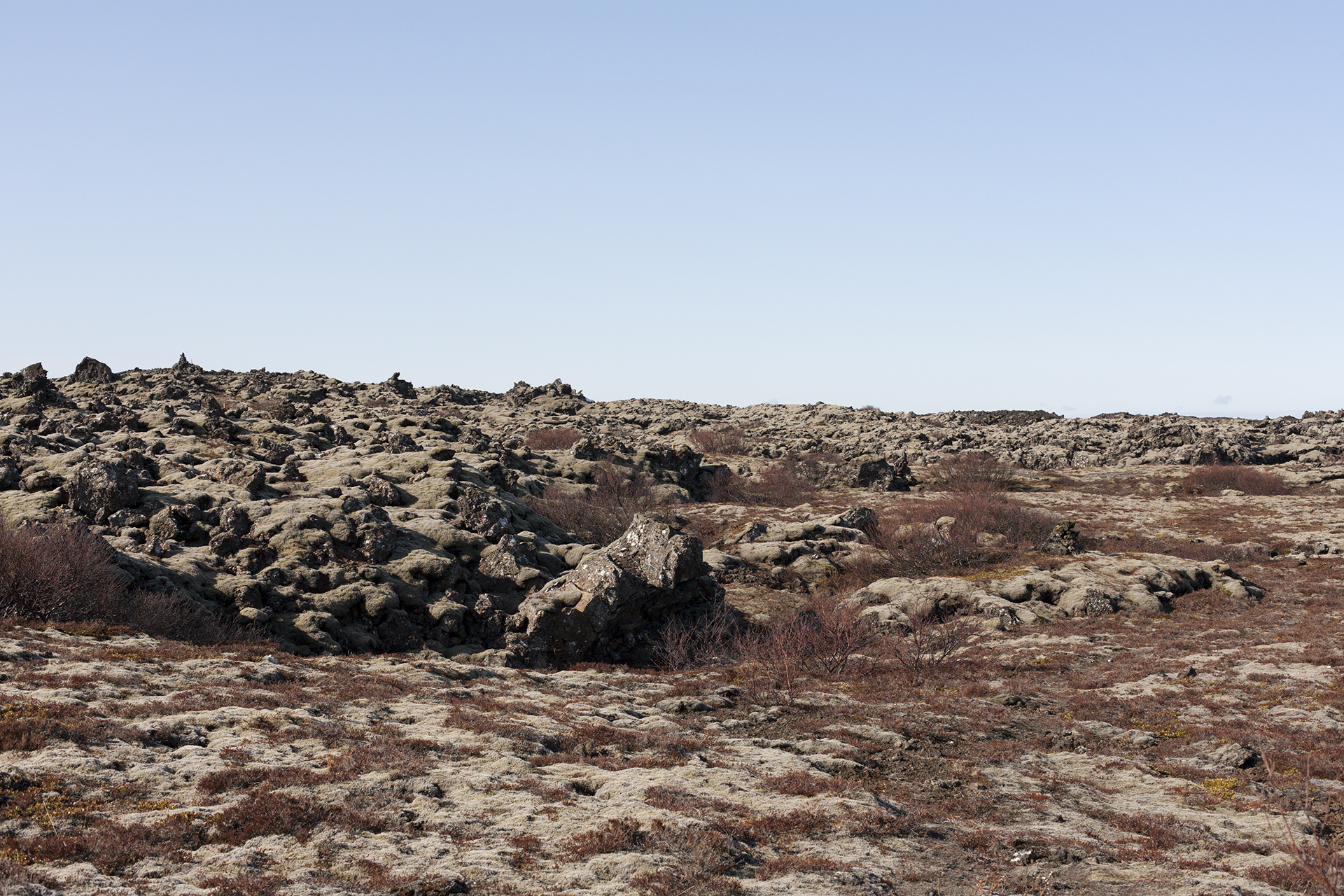

SW Iceland, 2015

What does “nature” look like? Can I get close enough to photograph it? And once I’d have captured “nature”, how can I be sure that I haven’t altered its essence in any way?

With a reasonable fluency in Icelandic, I went off the roads the Icelandic tourist industry paved for us foreign visitors. Caught in a dense network consisting of place names, maps, power lines, quarries and roads, the idea that there was a pristine nature on the other side of the impeccable brochures or websites became seriously dubious. That was in late 2013.

I came back in June 2014 and the Spring of 2015 informed and inspired by the discussions around the Anthropocene. I then set out to focus my attention on the Reykjanes peninsula in southwest Iceland, a relatively small area where two thirds of the country’s population live, thus where the pressure on the environment is felt and seen the most.

Affected by the not so uncommon urban sprawl and a furrowed by the North Atlantic ridge at the same time, the peninsula seemed torn apart between an avid desire to develop and a careful attention to the Earth tremors or the whispers of “hidden people” (Huldufólk in Icelandic).

I further explored the places, forms and residues that make nature tourism in Iceland possible.

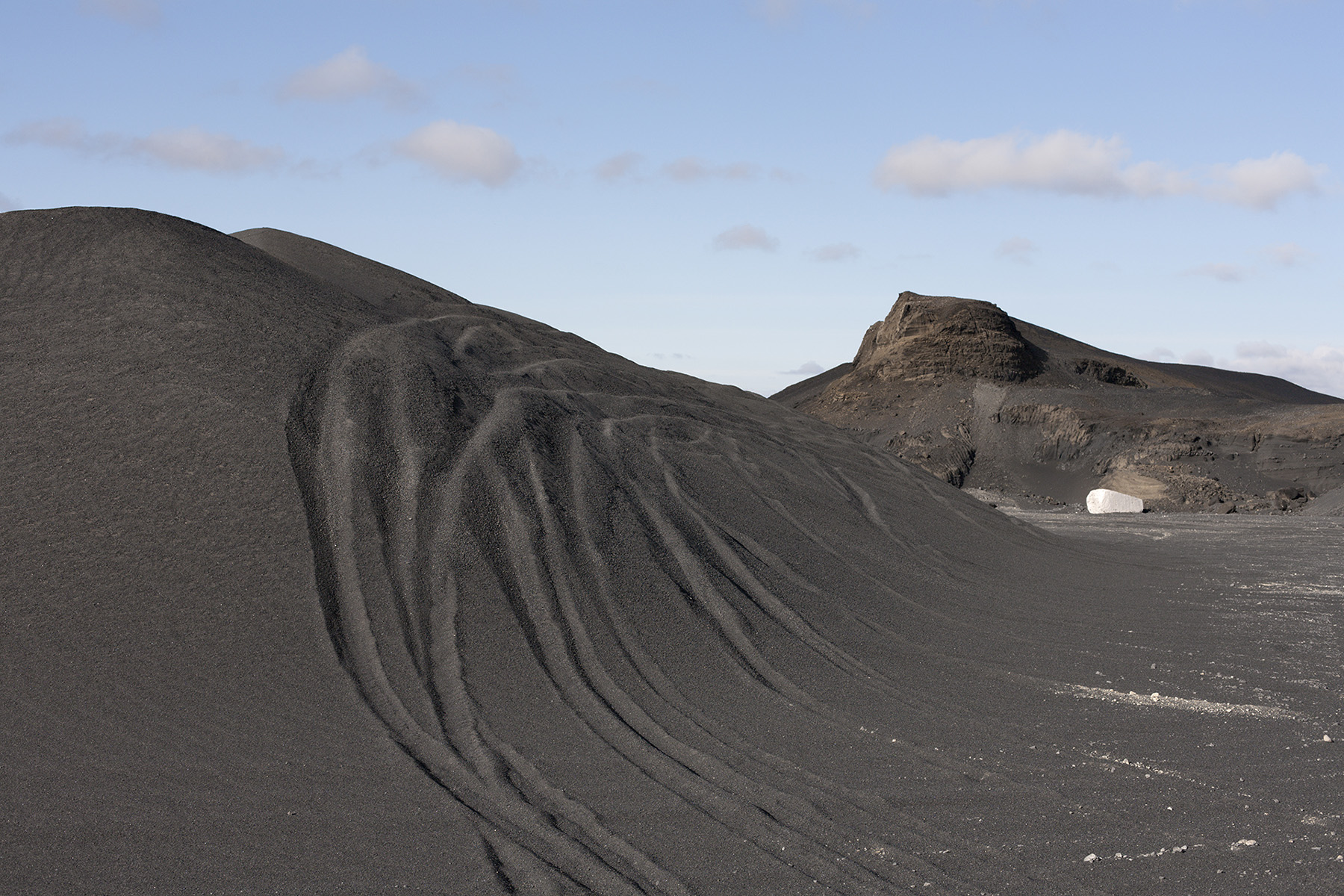

Hrauntungustígur walk